Today, digital screens and pages have conquered our world and even in education or work, information is often transmitted digitally, at the touch of a few keys or through voice commands. Paper and books seem quite common nowadays to the point of being outdated, however, their use is of fundamental importance for modern civilization. And it was not always given and easily accessible.

Before the invention of paper, people used various materials for writing, such as papyrus and parchment. Papyrus, a plant that resembles reed, grows on the banks of the Nile in Egypt. The Egyptians cut pieces of the skin of the papyrus trunk and after some processing, join them together to form long strips. As papyrus tore easily, during the time of the successors of Alexander the Great, the use of goat or sheep skin was invented. The skin was cleaned of wool and fat and after some processing with chalk, it was ready for writing. This skin was called parchment and it may have been more durable than papyrus, but it was also more expensive.

The Arabs, who had conquered the eastern coast of the Mediterranean, transmitted to the Byzantine Empire and the rest of the West a valuable Chinese invention, the production of paper.

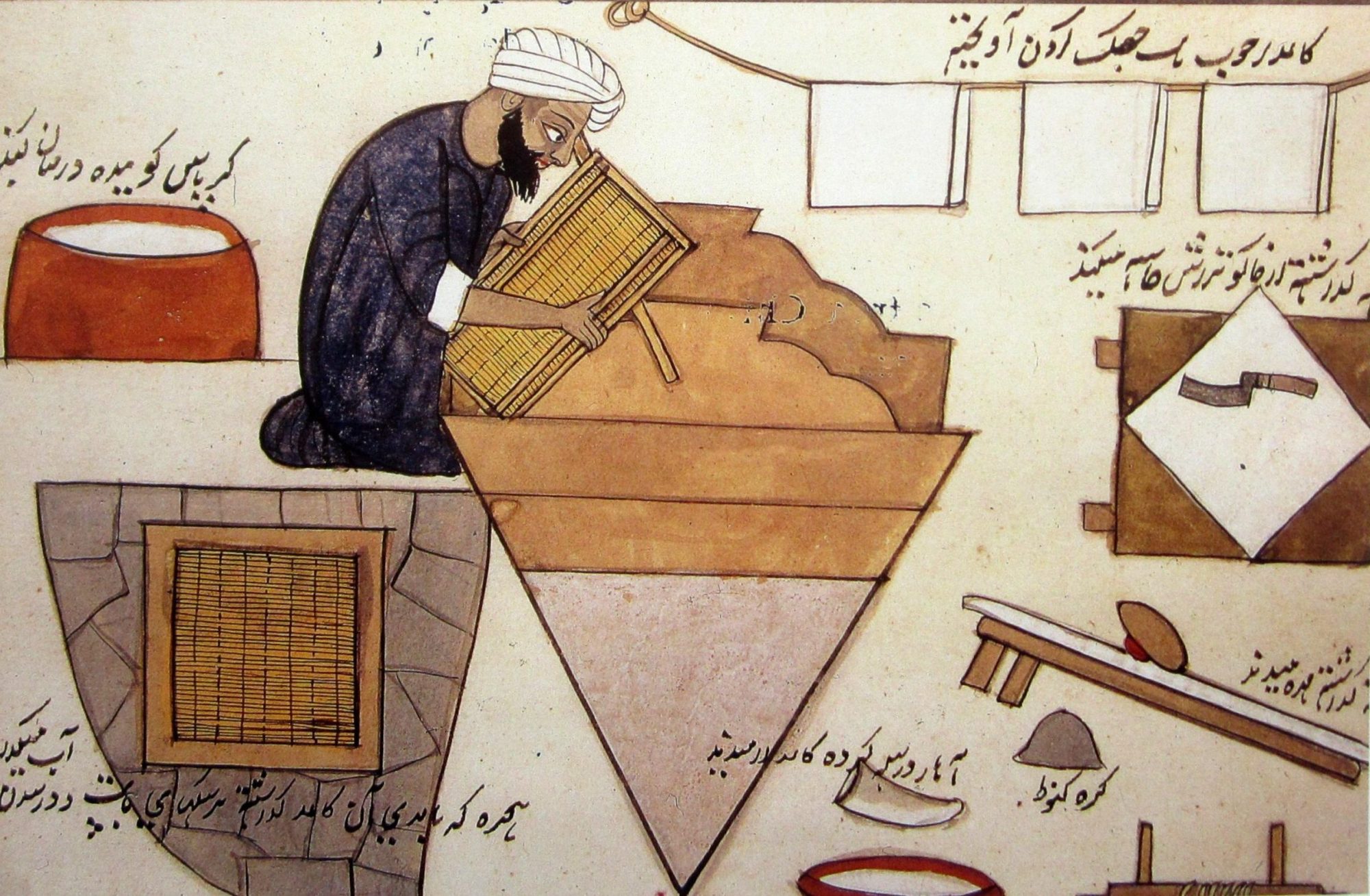

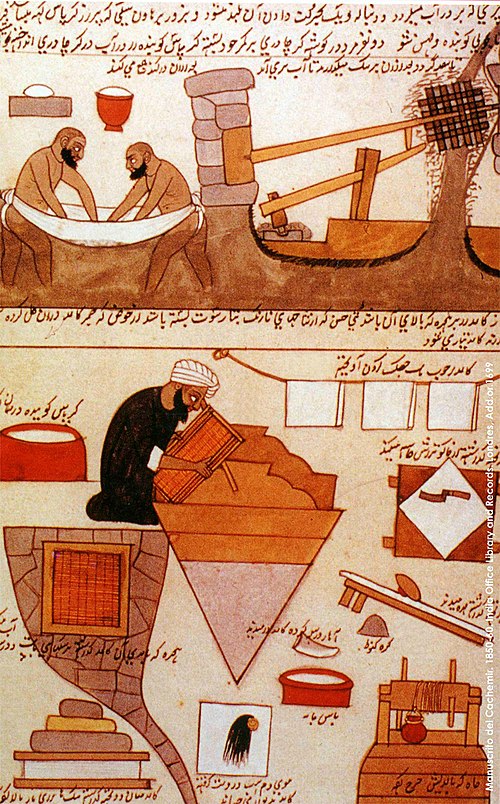

The invention of paper is traditionally attributed to the court official Cai Lun in 105 AD. Cai Lun improved the existing methods, using fibers from various materials, such as tree bark, bamboo fibers, rags, and fishing nets. The process involved crushing these materials into fibers, soaking them, and forming a thin, flat sheet, which was then dried. The art of papermaking remained a secret in China for centuries. However, after the Battle of Talas River in Central Asia in 751 AD, Arab captives learned the technique from the Chinese and then spread it to the Islamic world. Muslims used linen as a substitute for the mulberry bark used by the Chinese. Linen fabrics decomposed as they soaked in water, and prepared for boiling.

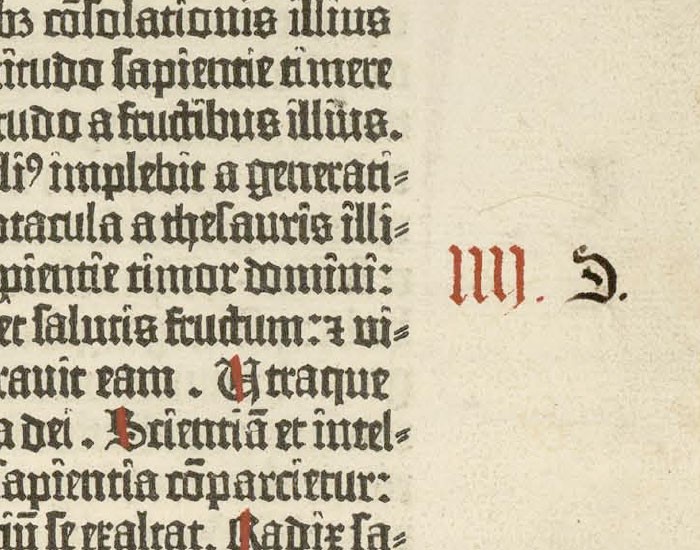

In the mid-15th century, the invention of movable type printing by Johannes Gutenberg dramatically increased the demand for paper and accelerated its spread. As production increased, paper became cheaper, widely available, and of better quality. From then on, paper became the only material for making books.

Initially, reading a papyrus was done by unrolling a roll, a process that was quite difficult – one hand to unroll the papyrus and the other to roll it up. For this reason, in the 2nd century AD a different way of making the book was invented. Scribes used to take several pieces of papyrus or parchment, and later paper, fold them in half and sew them together, creating volumes. Several volumes sewn together at the spine constituted the codex, that is, a handwritten book.

The ancient texts were passed down from generation to generation by copying. Specially trained scribes worked in bibliographic workshops for many days until they finished a book. Their tools consisted of pens, inkwells, a sponge for erasing, a knife for scraping the tip of the pen, scissors for cutting the parchment, and a compass for measuring distances. Scribes did not simply copy, but often decorated the manuscripts. During the Middle Ages, many monasteries had bibliographic workshops, where not only religious texts were copied, but also secular ones.

The effort put in by the codex, as well as the materials used, made the book expensive and rare. Some scholars had their own libraries and often lent or exchanged their books with others. Monasteries also had libraries, in which many thousands of papyri, codices and books have been preserved, which still offer valuable knowledge and great texts of human thought.

Considering all the miles traveled and the work done by thousands of people until ideas spread to the world and knowledge becomes a common good, books have a great value and have made a decisive contribution to modern culture. And many argue that despite the rise of technology, books will never be completely replaced in readers’ preference.