Al-Jahiz lived, during one of the most exciting times of intellectual history – the period of the transmission of Greek science to the Arabs and the development of Arabic prose literature -and was intimately involved in both.

Not much is known about al-Jahiz’s early life, but his family was very poor. Born early in February 776, some 14 years after the foundation of Baghdad by the Abbasid Caliph al-Mansur, al-Jahiz grew up in Basra (Iraq), a major intellectual center at that time which contributed substantially to al-Jahiz’s intellectual development. It was there that he first went to school – studying under some of the most eminent scholars of Islam. His family was poor and as a young man of 20 he seems to have sold fish along one of the Basran canals. Nevertheless, al-Jahiz learned to read and write at an early age, indicating the opportunities for what today’s sociologists would call “upward mobility” in eighth-century Iraq. While still in Basra, al-Jahiz wrote an article about the institution of the Caliphate. This is said to have been the beginning of his career as a writer, which would become his sole source of living.

He moved to Baghdad, attracted by the greater scope of the capital of the Arab Islamic Caliphate at the time, in 816 AD, because the Abbasid Caliphs encouraged scientists and scholars and had just founded the House of Wisdom. Due to the Caliphs’ patronage, his eagerness to reach a wider audience, and establish himself, al-Jahiz stayed in Baghdad (and later Samarra) where he wrote a huge number of his books. In Bagdad he was exposed to a new and important influence: Greek science, particularly Aristotelian thought.

The Caliph al-Ma’mun wanted al-Jahiz to teach his children, but then changed his mind when his children got afraid of his boggle-eyes. It’s said that this is where he got his nickname. The fact that he never held an official position allowed him an intellectual freedom impossible to someone connected to the court.

Over a span twenty-five years, he would acquire considerable knowledge on Arabic poetry, Arabic philology, and pre-Islamic Arab and Persian history. Additionally, al-Jahiz read translated books on Greek sciences and Hellenistic philosophy, especially that of Greek philosopher Aristotle. His education was highly facilitated due to the fact that the Abbasid Caliphate was in a period of cultural, and intellectual revolutions. Books became readily available, and this made learning easily available. Though paper had been introduced into the Islamic world only shortly before al-Jahiz’s birth, it had, by the time he was in his 30s, virtually replaced parchment.

The availability of a cheap writing material was accompanied by another social phenomenon, of which al-Jahiz himself was a product: the rise of a reading public. For the first time since the fall of the Roman Empire, the cities of the Middle East contained a large number of literate people – many of humble origins.

During his long lifetime al-Jahiz authored two hundred books that discuss a variety of subjects including Arabic grammar, zoology, poetry, lexicography, and rhetoric. Of his writings, only thirty books survive today – enough nevertheless to show the omnivorous curiosity of the author. Al-Jahiz wrote Levity and Seriousness, The Art of Keeping One’s Mouth Shut, Misers, Early Arab Food, In Praise of Merchants, Against Civil Servants, The Squaring of the Circle, The Merits of the Turks, and, perhaps the most important, the Book of Animal, receiving 5,000 gold dinars from the official to whom he dedicated it. The titles, however, give only a faint idea of their contents. Incapable of keeping to the point, al-Jahiz’s essays wander from anecdote to anecdote, digression to digression, until both he and the reader lose sight of the original subject entirely.

Despite his propensity to meander in prose, al-Jahiz was particularly interested in style and correct expression. “The best style,” he says in an essay on schoolteachers, “is the clearest, the style that needs no explication and no notes, that conforms to the subject expressed, neither exceeding it nor falling short.”

This interest in style was characteristic of a group of Basran scholars, who, during the late eighth and early ninth centuries, sought to preserve the linguistic heritage of the Arabs by recording the poetry and sayings of the Bedouin of the Arabian peninsula. This movement had unanticipated results: because of their almost anthropological interest in the language and customs of the Bedouin, and in the social conditions of Arabia during both the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods, the Basran scholars achieved a deep appreciation of Arabic grammar and pre-Islamic poetry. They went on to compose sophisticated commentaries on the Koran, critical editions of poetry and treatises on grammar, and to compile dictionaries and specialized word-lists. A master of these disciplines, al-Jahiz was one of the first writers of Arabic to work all the diverse preoccupations of the Basran scholarly milieu -grammar, prophetic tradition, rhetoric, lexicography and poetry-into a “literature” – that is, prose compositions to be read by non-specialists for pleasure and instruction.

Al-Jahiz never lost sight of his readers, and developed a very personal and characteristic style, which blended anecdote, serious subjects and jokes, in an effort to hold their interest. He described his style himself, saying: My books contain above all unusual anecdotes, wise and beautifully expressed sayings handed down by the Companions of the Prophet, sayings which will lead to the acquisition of good qualities and the performance of good works … they also contain stories of the conduct of kings and caliphs and their ministers and courtiers, and the most interesting events of their lives.

In Baghdad, al-Jahiz not only fused the Islamic sciences to Greek rationalism, but created Arabic prose literature. He showed that Arabic was flexible enough to handle any subject with ease, and although he was not personally associated with the House of Wisdom, his linguistic achievement paralleled – indeed surpassed – the efforts of the scholars engaged in rendering Greek scientific texts into Arabic.

Bagdad was exposed to a new and important influence: Greek science, particularly Aristotelian thought. His works attest the remarkable spread of Greek ideas among ordinary readers. Both in his subject matter and vocabulary, he presumes a familiarity – albeit superficial – with Aristotle and the technical terminology of scholastic theology. He tells many anecdotes of the scholars of the House of Wisdom, many of whom appear to have been his friends.

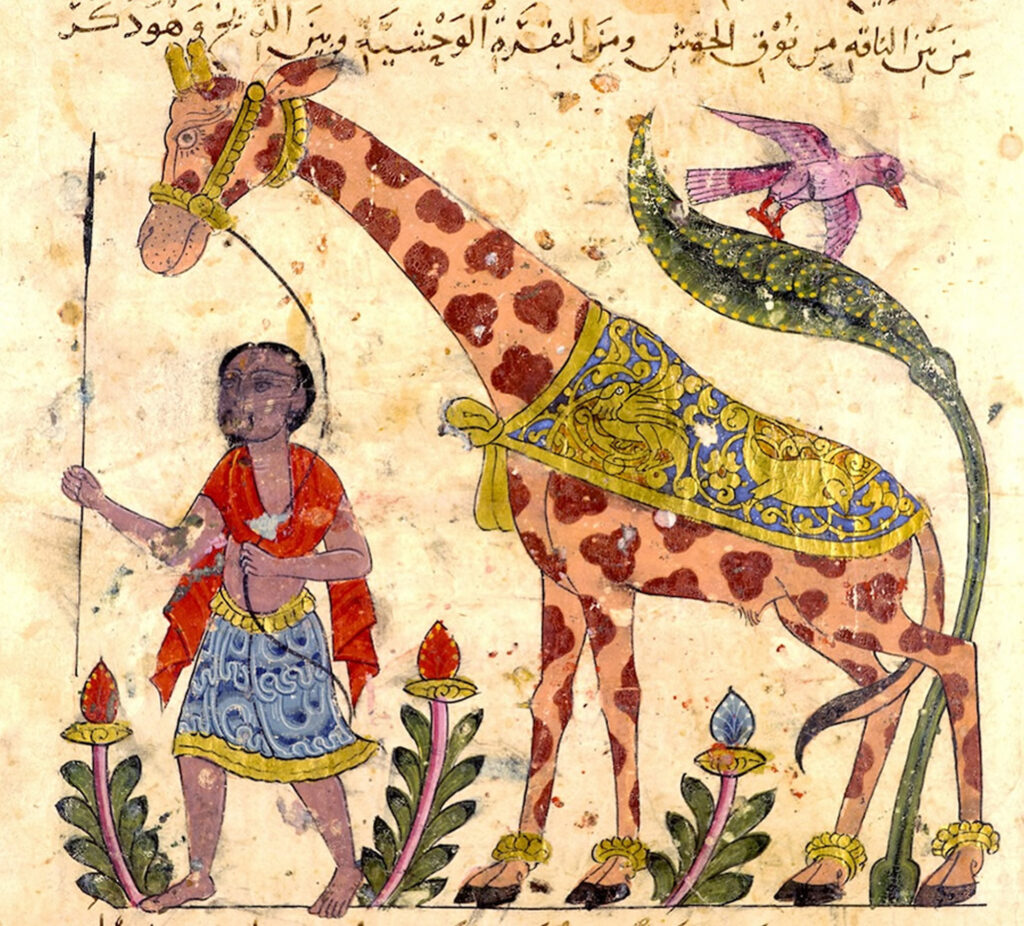

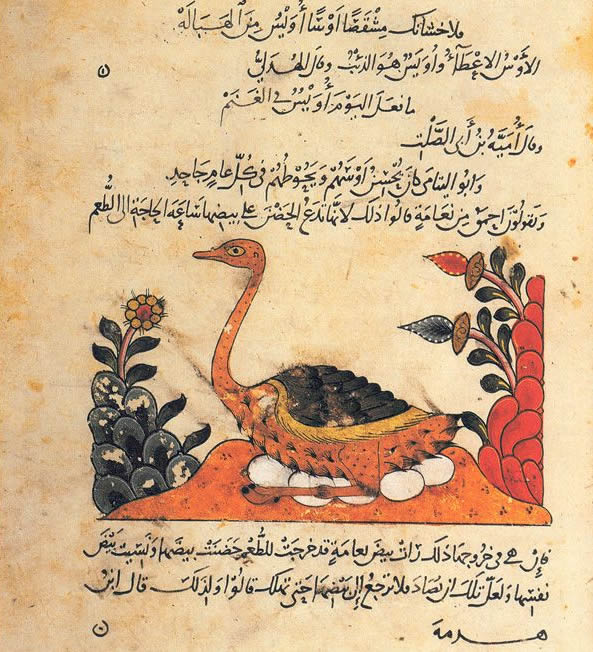

The book that best illustrates his method is his Book of Animals – Kitab al-Hayawan – which, even incomplete, runs to seven fat volumes in the printed edition. Despite the title, the Book of Animals is by no means conventional zoology, or even a conventional bestiary. It is an enormous collection of lore about animals – including insects – culled from the Koran, the Traditions, pre-Islamic poetry, proverbs, storytellers, sailors, personal observation and Aristotle’s Generation of Animals.

But this is by no means all. In keeping with his theories of planned disorder, he introduces anecdotes of famous men, snippets of history, anthropology, etymology and jokes. The “literary” quality of the Book of Animals, however, should not obscure the fact that it contains scientific information of great value. Anticipating a number of concepts which were not to be fully developed until the time of Darwin and his successors, al-Jahiz toys with evolutionary theory, discusses animal mimicry – noting that certain parasites adapt to the color of their host – and writes at length on the influences of climate and diet on men, plants and animals of different geographical regions. He even gets into animal communication, psychology and the degree of intelligence of insect and animal species. He gives a detailed account of the social organization of ants, including, from his own observation, a description of how they store grain in their nests in such a way that it does not spoil during the rainy season. He knows that some insects are responsive to light – and uses this information to suggest a clever way of ridding a room of mosquitoes and flies.

The bewildering variety of its contents, in fact, has always daunted translators, and later natural historians. Al-Damiri, who lived in the 14th century and wrote a well-known encyclopedia called The Lives of the Animals, used much of the scientific and linguistic information from al-Jahiz, but eliminated the anecdotes, poetry, digressions and jokes. His greatest service, perhaps, was in popularizing science and the rational method, and in showing that a literary man could concern himself with any subject.

A devout Muslim, al-Jahiz regarded the physical world as the visible sign of God’s will. His purpose in writing the Book of Animals was not merely to entertain, but to lead his readers to an appreciation of the wonders of God’s creation, which he believed to be as manifest in the most insignificant as in the grandest:

I would have you know that a pebble proves the existence of God just as much as a mountain, and the human body is evidence as strong as the universe that contains our world: for this purpose the small and slight carries as much weight as the great and vast.

Sadly, few works of al-Jahiz have survived the vicissitudes of time, but those that have, make us regret all the more the ones that have been lost. Together they present a faithful and lively portrait of Baghdad and Basra during the Golden Age of Islam. He writes of singing girls, vagabonds, scholars, theologians, caliphs and viziers, and a very detailed picture of everyday life in ninth-century Iraq could be extracted from his works. More importantly, he communicates to us the excitement of an intelligent non-specialist confronted with radical scientific, philosophical and theological speculations. Baghdad and Basra were awhirl with ideas, and al-Jahiz is very funny about the pretensions of people who studded their conversation with technical terms like “atom” without in the least understanding what an atom was.

At the same time, al-Jahiz enthusiastically supported certain aspects of the Greek tradition, by which he meant primarily Aristotle. He believed in the scientific method – as it was then understood – and applied reason and logic to observed phenomena. Loving a good story, however, al-Jahiz could never resist passing on the most preposterous yarns of sailors and Bedouin.

This lack of rational plan, so much a feature of his works, may have been at least partly deliberate, since his greatest fear was boring his readers. This does not mean that he was never serious, but that in all his major works, seriousness and humor are inextricably mixed; it is sometimes difficult to know when he is joking and when he is not. It is also difficult to pin al-Jahiz down on a given topic, for he loved to present debates between two social classes – scholars and merchants, mules and horses for instance – in which the merits of each are paraded before the reader. What the author himself thought is often not obvious, and it is possible that in these dialogues he was primarily interested in showing his skill at taking both sides of an argument.

He had a great love of books, and his Book of Animals begins with a long passage in their praise. It would have saddened him that so many of his own have perished, but he would have been delighted, one feels, with the manuscript from which the illustrations that adorn this article are taken.

This manuscript, which dates from the 14th century, was discovered in the Ambrosiana Library in Milan in 1939 by the Swedish scholar Oscar Lofgren.

The Ambrosiana manuscript is textually very important. It is obviously copied by an educated scribe who has indicated the vowels – not normally written in Arabic – which allow the text to be more accurately understood than heretofore. This is doubly important as few manuscripts of the Book of Animals survive, and the Ambrosiana manuscript is among the earliest of those that do.

Even more important than the text, however, are the superb miniatures which illuminate it. Illustrated Arabic manuscripts of any sort are extremely rare, and this is the only illustrated copy of a work by al-Jahiz in existence. The 30 miniatures, done in a deliberately archaizing style – perhaps imitated from an earlier illustrated manuscript from al-Jahiz’s native Iraq – were done at the high point of Arabic manuscript illumination: 14th-century Mamluk Egypt. The style of the miniatures, consciously old-fashioned, succeeds in capturing the mood of al-Jahiz’s prose -they are lively, highly colored and gently humorous. One cannot help feeling that al-Jahiz would have liked them, especially in view of his own admiration for the pictorial arts of the Byzantines and the Chinese – which he mentions in the Book of Animals.

Al-Jahiz returned to Basra where he died in January 869. His exact cause of death is not clear, but a popular assumption is that Jahiz died in his private library after one of many large piles of books fell on him, killing him instantly.