The bath in antiquity

It is not known exactly when the man started using enclosed spaces for his cleanliness, but there are some references which indicate it existed as a practice in India, in ancient Egypt and later in the ancient Greek civilisation. Homer’s heroes were relieved by a warm bath after many long and tough battles, while Hippocrates, in his medical work About Gases, Places, and Water, dedicates a chapter to the process of hydrotherapy.

The Assyrians and the Hittites left some building signs of baths, while the first baths with hot and running water appeared in Athens, approximately in the 5th century BC. The “gymnasia”, the exercise areas for young men, were equipped with baths, where the athletes used to wash after their exercise.

Roman baths – thermal baths

The custom of separate structures for bathing was established by the Romans. Public bath facilities were among the most advanced technological building complexes in all regions of the Empire, signalling the basic concept of its cultural identity. Cleaning and relaxation areas, meeting and entertainment venues, the Roman “thermae” are found in every city of the powerful empire.

The thermae mainly consisted of the changing room, the hot water swimming pool (spogliatorio), the lukewarm water pool (tepidarium), the cold-water pool (frigidarium), and sometimes the palestra, an open sports area. A typical example of the architecture and structure of a Roman bath, the thermal baths of Caracalla in Rome, were covering 118,000 m². The decoration of the halls was varied and rich. Luxurious marbles, mosaics, columns, sculptures, frescoes adorned the Roman thermae with taste.

It is believed that in the 1st century BC a Roman architect, Sergius Horace, was the first who used an air heating system for the bath function. In 33 BC, there were 170 baths in Rome. The expansion of the Roman Empire transferred the bath habit in the whole region and thus similar public, or private buildings were constructed in England, North Africa, Asia Minor and Middle East.

Byzantine baths

The bath habit was continued from the Roman Empire to Byzantium, with the construction of baths of great social and architectural significance. The baths during the Byzantine era were privately owned, publicly built in the central parts of the cities, and monasterial, built in or near the monasterial enclosures. The Byzantine baths, apart from cleaning and care sites, were also places for social life, especially for the women, who were able to chat and associate there.

As in Rome, so in Byzantium, public baths were usually well-built and captivating. They were structured in three parts, the first with the cold water, where the preparation was made, the second with the lukewarm water, where the cleaning was done, and the “inner dome” with the hot water, where the sweating and the deep cleansing were done. Of course, the baths were equipped with hot and cold-water tanks. The most important baths in Istanbul were those of Zeusippos.

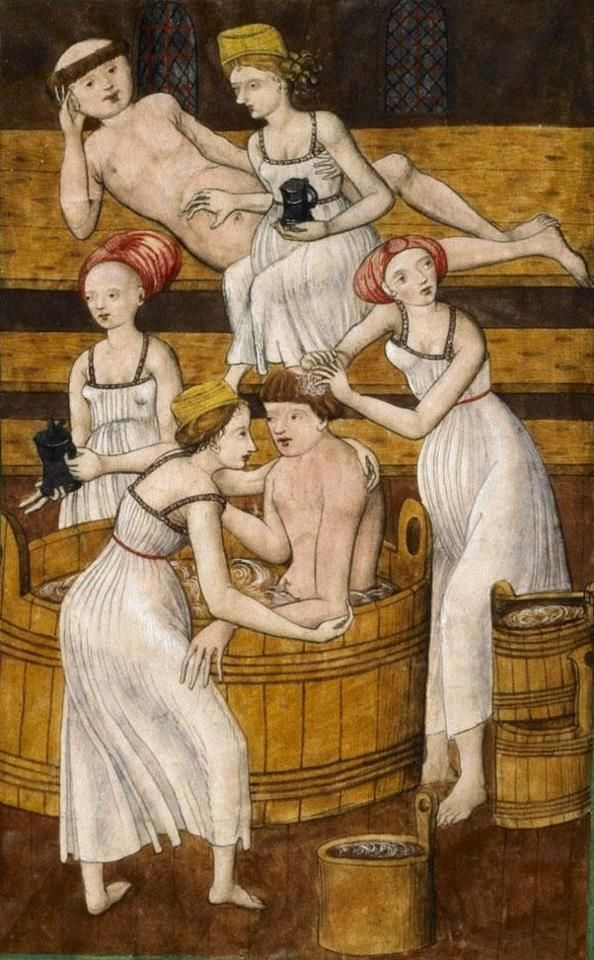

The bath in the medieval West

The fall of the Byzantium changed the bath habits in the West, with the bathtubs being replaced with the large baths. In some cases, the Catholic Church banned the body washing by limiting it in a monthly frequency. In the 11th century, the bathroom was considered as a space of the devil and a cause of disease transmissions.

In 1536, all the public baths of Spain were destroyed, while Louis 14th was bathed only every spring. At the same time, European writers attributed the skin sensitivity of the women of the East to the frequent and disastrous bath.

The bath in the Middle East

Obliged by their religion to have the body cleanness, people of the East very soon adopted the Roman and Byzantine bath habit. In the 8th century, the first bath was built in Syria by the dynasty of Umayyad, which imitates accurately the Byzantine architecture.

In Damascus, in the 14th century, 60 baths were functioning and in Baghdad 40. In Aleppo, there were 68 public baths registered from the 13th century, while the traveler and writer of the 17th century Evliya Celebi noted 55 baths in Cairo.

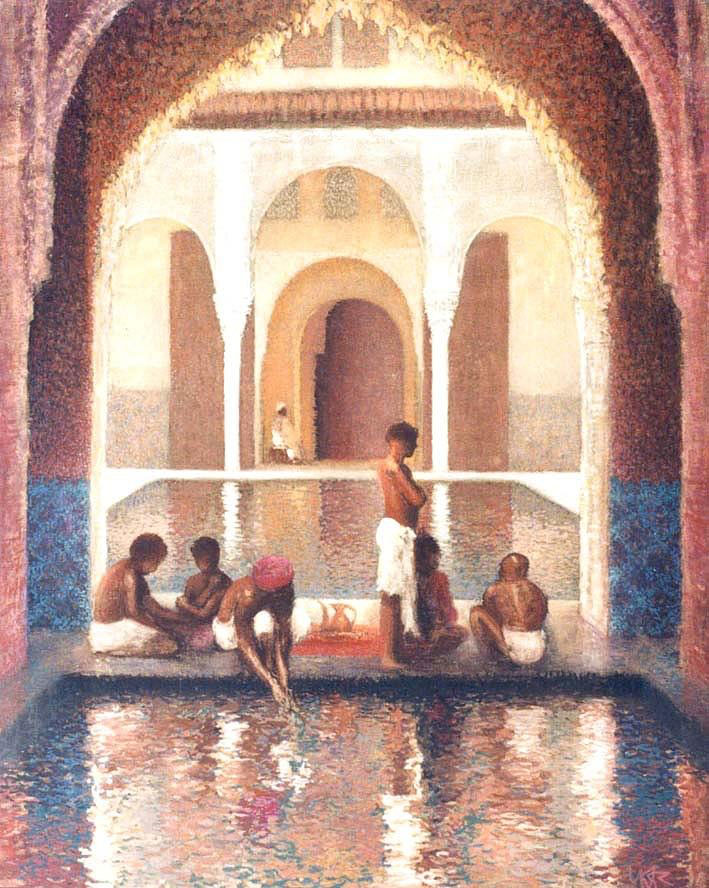

The oriental hammam

After the conquest of Istanbul, Sultan Mehmed built 19 baths, many of which on some previous Byzantine constructions. In the 17th century, in Istanbul, 168 hammams were functioning, the largest of which could serve 5.000 bathers. A more recent list of 1886 counts 237 hammams.

During the Ottoman period, the hammams were often parts of large building complexes, called “kylliye”, which were including a prayer room, a medical centre, an Imaret (soup kitchen), a library, a school, and a housing space for students and teachers, or travellers. Revenues from the baths of kylliye – which always had public benefit purposes and belonged to the Sultan, as well as to members of the royal family, or to eminent dignitaries of the Empire – were used to cover the costs of the Imaret.

The Ottoman hammam consisted of three parts: a hall, the changing room, which was heated warmly, a second room, which was heated moderately and had benches around for the bathers to rest, and a third very warm room, which had faucets. There weren’t any swimming pools, but individual bathtubs and plenty of water. In a large changing room, the bathers could rest and relax, while enjoying their friends’ company.

As the time went by, the bath habits of the East have not declined. On the contrary, baths continued to play an important role in the social life of both men and women. At the beginning of the 18th century, Europe rediscovered the bath of the East. Forgetting the Roman and Byzantine baths, travellers and diplomats, who were coming in contact with the East, called them “Turkish baths” and hammams.

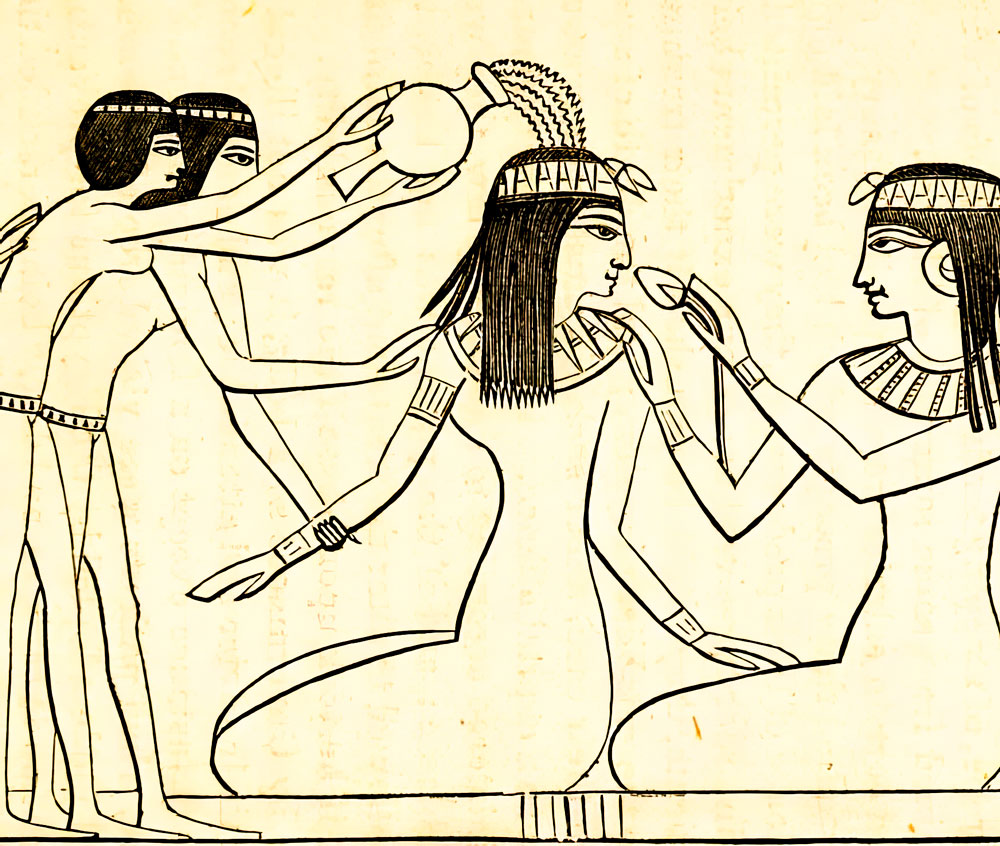

The grooming of the women of East

The women of the East were famous for their bright and silky skin. Washing and cleansing with water were not only a religious obligation, but also a passion for the appearance and a luxurious leisure. The ritual of the hammam used to include everything useful for grooming, perfuming, and sensual mood. It used to begin in the morning and to end in the evening, after complicated processes of several hours.

Julia Pardo in Beauties of the Bosphorus describing scenes from hammam of 1830 formed “a spectacular dreamy image, making me doubt if what I saw was actually the creation of a confused mind”. The women rubbed their skin with natural sponges, showered their hair with egg yolks, used the white eggs to eliminate wrinkles around their eyes. “It’s not easy to define the beauty of Eastern women” proclaims Edmondo De Amicis in 1896 in a travel book. Almond and jasmine creams, roses and spices were used in the premises of hammam to increase women’s charm. Sandalwood, frankincense and myrrh flavored their bodies, while they simultaneously prevent from the “evil eye” (Samuel Baker).

Almond and jasmine creams, roses, and spices were used in the premises of the hammam to increase the women’s charm. Sandalwood, frankincense and myrrh were flavouring their bodies, while they simultaneously were preventing them from the “evil eye” (Samuel Baker). Each woman was carrying huge varieties of fragrances, essential oils and creams. They were testing and exchanging their beauty secrets. They were making depilatory creams from fossil and they were using “mothers of pearls” to remove them.

For the women, hammam meant to be an endless list of things that they should have with them. Therefore, for the older ladies, hammam expenses were along with jewels, the most serious investment in the family budget of the harem – gold and silver hubcaps to throw water on their bodies, silk towels embroidered with semi-precious stones to cover themselves, pearls to knit their hair, ivory comb to comb them, white pure soaps in ornamented sheaths, yoghurts prepared with fresh fruit to quench their thirst, water pipes to smoke after the bath.

They didn’t use bathtubs, due to the superstition that the stagnant water contains “ifrit” (evil creatures). They walked onto wooden shoes (clogs), real pieces of art, decorated with pearl and precious stones, which were protecting their feet from the hot marble bath and were reducing the risk of slipping, by protecting them from the jealously jeans, hidden in the secret, dark corners of the hammam.

Top Kapi’s files mention that every woman was consuming for her bath a quantity of water which would suffice 100 men. Venetian, French, and Egyptian merchant ships, traveling protected by Algerian corsairs, were carrying the precious cargoes, first to Constantinople, even from the time of the Byzantine emperors, and much later to the West. Smells of herbs and massage with essential oils, pomades of fruits, potatoes and nuts, honey and yogurt, mixed with art, mysticism and mastery, created a myth around the women of the East and made them a fantasy in the puritan and pietist Europe.