Like other aspects of Islamic culture, Islamic art was the result of a combination of peoples and civilizations, with Arabic, Persian, Mesopotamian and African traditions getting intertwined. Starting from this basis and rejecting the depiction of living creatures, Muslim artists gradually established a style of their own that essentially diverged from the Roman and Byzantine art of their time. Three types of decoration stand out as the main features of Islamic art: floral compositions, geometric shapes and calligraphy.

The use of plant motifs in Islamic art is, of course, dependent to some extent on the Islamic prohibition on the representation of living creatures. The representation of nature is more abstract than realistic as in Western art. In plant imagery, plants, branches, leaves and flowers are intertwined, interconnected and often indistinguishable from the geometric lines around them, as in arabesques. Muslim artists use foliage with particular delicacy, especially around arches and windows. The use of floral motifs has been extended to many decorative objects, such as ceramics, textiles, carpets and the colourful tiles that often cover large surfaces in religious or public places.

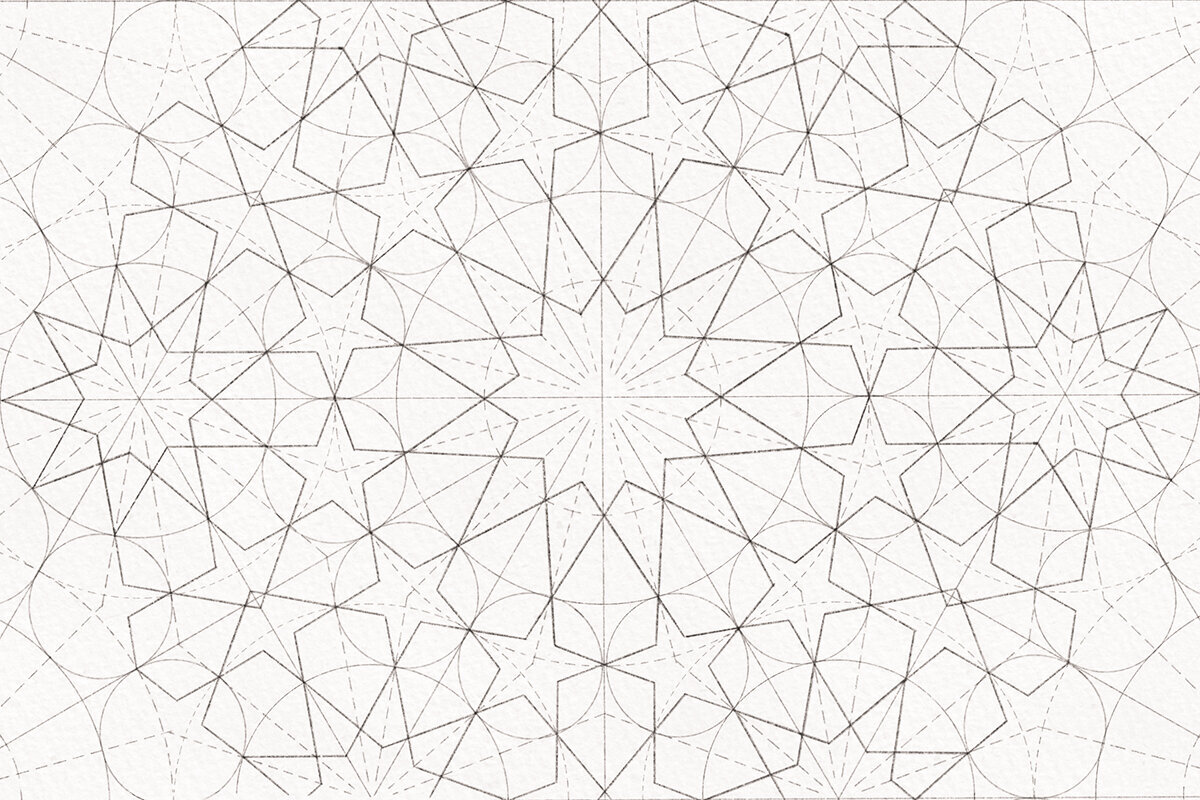

Geometry also plays a dominant role in Eastern art, allowing artists to unleash their imagination and creativity. One reason for the development of geometric art was the complexity and popularity of the science of geometry that flourished in the Islamic world. A new art form therefore emerged, based entirely on mathematical rules and geometric shapes such as circles, squares, triangles and stars. Large structures, palaces, mosques, baths and gardens follow the measures of geometry and symmetry. On a smaller scale, carpets and kilims became canvases to develop patterns with geometric precision.

The development of calligraphy as a decorative element is due to the importance Muslims attach to their holy book, the Qur’an, which promises divine blessings to those who read and write it. This shows that the aim of Islamic calligraphy was not only to decorate, but also to adore and honour God. Similarly, in Christian art, the depiction of God’s image, iconography, is considered a divine act. On the other hand, in aniconic Islamic art, the transcription of God’s word in the most beautiful calligraphic letters is considered a divine act. Calligraphic texts adorn not only books and letters, but also religious buildings, public monuments and tombs.

Many Muslim artists have lived and died in complete obscurity. In European Medieval as well as Oriental art, it was the exception rather than the rule for an artist to sign his work with his name. What mattered was the result of his work, not his identity. The knowledge of sciences and arts, inextricably connected, was incorporated within the craft guilds, which were the organising bodies that created traditional art.

Western scholars have often recognized the art of the East as limited, with reduced artistic creativity. Islam was seen as limiting artistic talent and its art was often judged by its prohibition to produce forms and dramatic scenes. Yet they were judging with the criteria and rules of the West. In reality, the Islamic art has a radically different perspective and value. Objects of Islamic art began to be traded on the trade routes connecting Asia with Europe: silks, muslins, carpets and ceramics. Thus, Europeans became acquainted with and fascinated by the art of the East, incorporating it into their fashion, buildings and daily life.