“There is a certain divergence between the popular image of Islam, as the religion that emanated from the desert and carried its ethos, and the notion of the garden: lush, green, shaded, moist, and fragrant, among other pleasant qualities that are all antithetical to the desert environment. But it seems that precisely because Islam came out of the desert that gardens occupy a substantial space in the Islamic imaginary and in the history of Islamic design.”

Nasser Rabbat, Director of the Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture MIT

From Spain and Morocco in the West to India in the East, Islamic gardens have never ceased to fascinate. Unlike European gardens, which are usually designed for strolls and social gatherings, Islamic gardens are meant for rest, contemplation and meditation. They represent the small oases in the “desert” of life, full of greenery, shade and water, fairly represent paradise. After all, the image of paradise as a garden is common to all three Abrahamic religions that originated in the Middle East, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

Islamic gardens are traditionally enclosed by walls, an influence from Persian architecture. They present symmetry and harmony, features always loved in Islamic art. The irregular flow of water and the angles of sunlight become the main tools that create a mysterious and sensory experience.

Running water together with aromatic plants, primary elements in every Islamic garden, stimulate the senses and the human intellect. Water is the origin of life. It serves as a means of physical and emotional cleansing and rejuvenation. It is recycled into fountains, to provide movement and melodious sound to the tranquility of an Islamic walled garden, turning into life its imposing atmosphere. At the same time, fruit trees and exotic flowers contribute to the aromatic appearance of the garden: cherry trees, peach trees, almond trees, jasmine, roses, daffodils, violets and lilies. With their constant blooming and withering, they become symbols of human life.

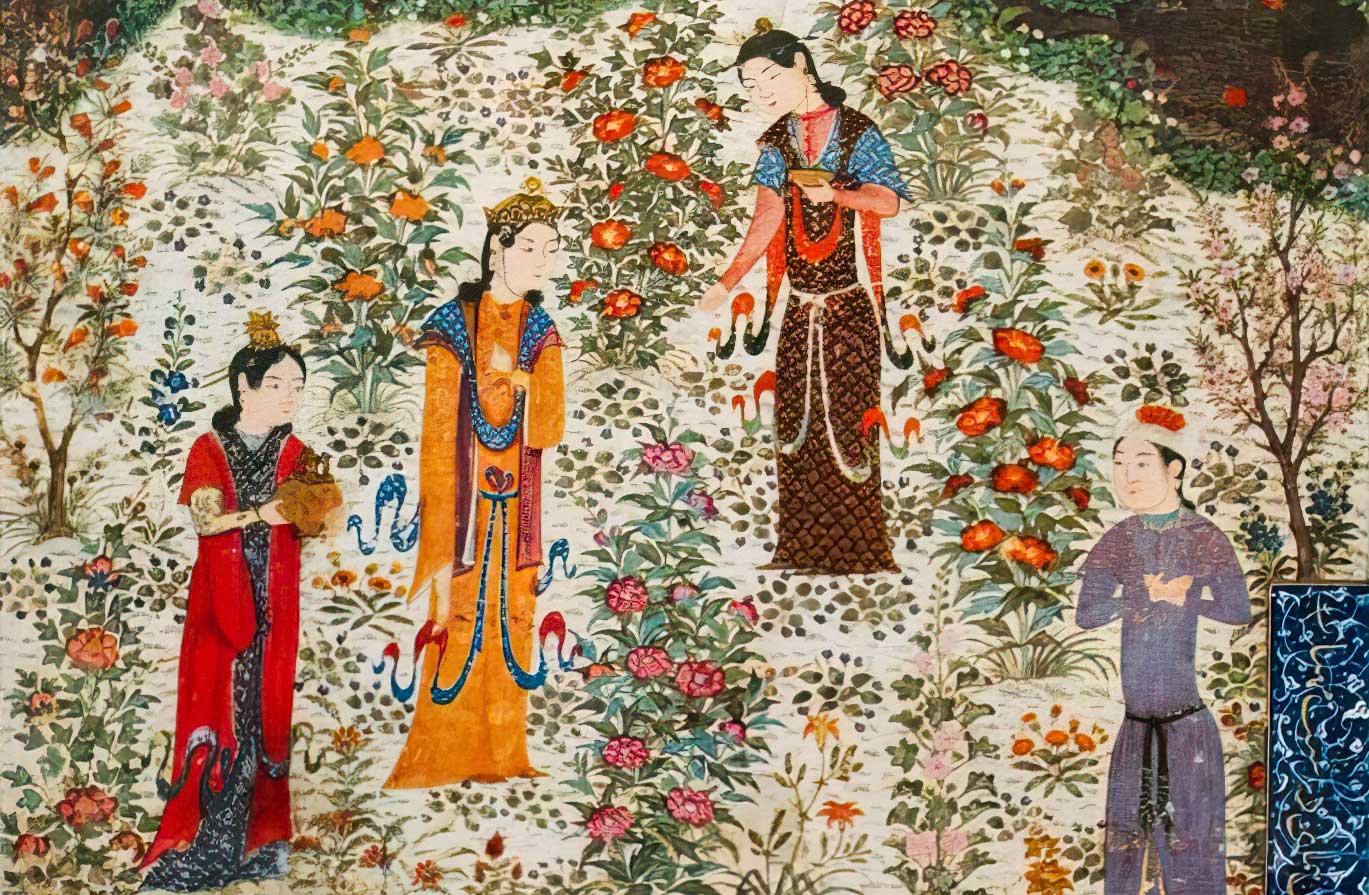

For the medieval Islamic world, gardening was a respected occupation. The Muslims recreated the Hanging Gardens of Babylon on a smaller scale. They built labyrinths, arcades, hidden fountains. They represented texts on the ground using beautiful flowers. They acquired such skill in the cultivation of roses that, at all seasons of the year, they bloomed in abundance. European travelers and traders were fascinated by the exotic plants of the East and, via terrestrial and marine Silk Roads, tried, often without success, to transport and cultivate them in the West.

In plant decoration, there were no superiors. They decorated with colourful flowers and intricate branching utensils, carpets, textiles, ceramic tiles that covered vast surfaces in mosques, madrasahs, hammams and residences. The detailed designs of the tapestry reproduced an inexhaustible variety of flowering plants, whose hues blended in perfect harmony.

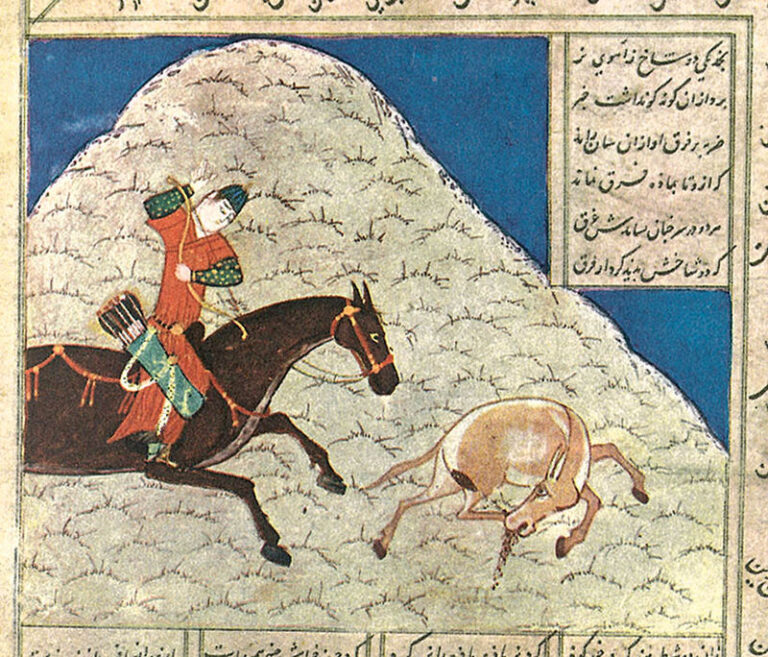

Many times, Islamic gardens were a hunting ground for the princes of the caliphate, while the size of the gardens symbolized the power and wealth of their owner. The royal gardens contained an endless variety of plants, both endemic and exotic, cultivated for their exquisite foliage, pleasant fragrance, or culinary and medicinal value.

Many Muslim scholars, through their study of plants, contributed to the knowledge of them, their diseases and methods of growth. They classified them into those that grow from cuttings, those that grow from seeds, and those that grow by themselves. They combined the rose with the almond tree to create rare and wonderful flowers.

All this endless knowledge of phytology still allowed them to study botany in combination with pharmacy and medicine. The analgesic and healing properties of plants, especially herbs, were analyzed in countless medical textbooks of the Islamic world, with Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine remaining for centuries the encyclopedia of the medical schools of the Middle Ages.